Meat For The Mind

Bison And The Spiritual Revitalization Of The Sioux And Assiniboine

Native News,

Mike Matthews was 46 when he saw his first free-roaming buffalo. It was in the 1980s, but he still remembers how the animal wandered just north of the Missouri River that flows through the Fort Peck Indian Reservation.

That bison was among the first of its kind back on the Northern Great Plains after a man-made extinction that saw the animal disappear from the region for more than a century.

Nearly 30 years later, he shot one.

Matthews had hunted since he was a boy living in Oregon with his mother and stepfather. On the day he was to shoot a bison, he was a father and grandfather, living back in Montana and looking to fulfill a bison lottery his daughter had won.

They left for Turtle Mound Ranch in December 2018. The herd was nearly two decades old after buffalo started returning to the Sioux and Assiniboine tribes of Fort Peck from their sister tribes at the Fort Belknap reservation.

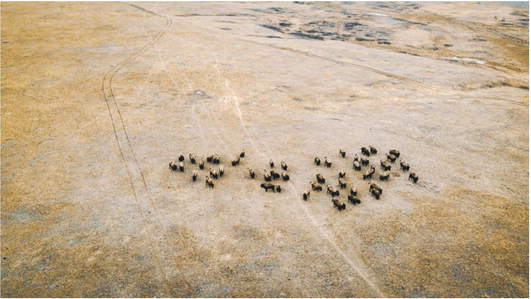

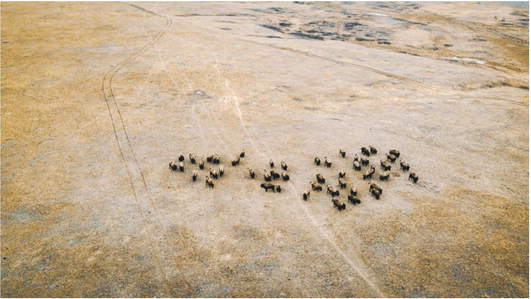

The snow turned the 13,000 acres set aside for the grazing animals white, bald and empty. Pockets of family groups that the buffalo arrange themselves into stood in contrast: horned, hulking and curious.

Matthews and his daughter agreed on a bull. He aimed his 45-70 lever action rifle.

In the Nakota Lakota spiritual hierarchy, the buffalo is the chief of the animals, and a relative of all the people who the U.S. government labeled as Sioux. A society exists for those who receive visits from buffalo in their dreams-and those who hunt them.

“I always thought they were a beautiful animal,” he said. He recalled when he and his daughter identified their target. “I didn’t really want to do it.” Still, he fired and killed the beast.

“I said a little prayer for him and he stopped, turned around and stood there waiting,” he said. Matthews fired four shots total. Two went through the bull, and two were dug out of the animal’s meat during processing. He saved both, along with the skull, the hide and the meat.

It was an 800-pound kill. One that supported Matthews and his family with food through six seasons. Still, the experience haunted the hunter.

“I won’t do it ever again,” he said.

Matthews’ guilt is not displaced. In several plains tribes, including the Assiniboine, the buffalo is revered. In the Dakota/Lakota/Nakota Sioux language, the word for buffalo, “tatanga,” translates to “buffalo people.”

The slaughter of the buffalo signaled the end of the Indian Wars, when the Plains Indians lost their source of food, shelter and culture that the animal provided. The animals, which were so essential to plains tribes, were nearly slaughtered from extinction in a strategic government effort to curtail the tribes by promoting mass hunts of the bison.

It’s 2020, and the presence of the buffalo has proven to be a reciprocal relationship. The Fort Peck tribes have been among a number of tribes across the country reintroducing the bison to their traditional grazing lands. The effort is showing physical benefits to the land. It is also proving how essential the animal is as both a food source, but also a wellspring that nourishes intangible notions like cultural connection and tribal identity.

There is a reason the bison has become such a prolific ad romanticized icon in both American and tribal art over the centuries. The bison is deeply engrained in the land and therefore the people who live on it.

McAnally, a founder president of Fort Peck Community College, said the restoration of the buffalo is part of a “great resurgence in spiritual awareness for Indian people.”

That resurgence intersected with modern treatment when he and other researchers began compiling responses from tribal members to the buffalo’s return.

“In our culture, they’re the chief of the animals, and they’re one of the lesser gods, so for me it’s not hard to see how important they are and why they are so remembered,” said Lois Red Elk-Reed, an 81-year-old poet, educator and grandmother in Fort Peck. “I have a hard time understanding white people, and the slaughter of the buffalo. Maybe that is something that nags their senses.”

Red Elk-Reed saw a live buffalo as a toddler at the Woodland Zoo in Seattle. She grew up speaking the three different dialects of Dakota/ Lakota/Nakota. She also helped launch a grassroots organization that spearheaded the revitalization of the buffalo at Fort Peck, the Pte’ Group, named after the female bison.

“I like the word ‘reciprocal,’ or ‘revitalization’ instead of ‘rehabilitation’ when it comes to the buffalo,” she said. “When I think of rehabilitation, I think of somebody’s who’s wounded.”

Red Elk-Reed was one of the consultants in a 2018 study on the relationship of the bison and the nations at Fort Peck. The study describes the bison as providing tribes with “nutrition for the spirit.”

“You know, millions of people feel that their dogs and cats are members of their families, and they would go for great expense to keep them alive and keep them happy,” said Robert McAnally. “You know, that relationship is easily acceptable by today’s society. But the relationship for the buffalo or an elk or a deer or a bear or even birds as that sort of relationship is very difficult for people to comprehend, even for young Indian people.”

Matthews was born on the Assiniboine and Sioux Fort Peck Indian Reservation and grew up in Oregon. He hunted with his stepfather in the forests of the Northwest, following in step until he was old enough to carry a rifle.

“Well he hunted. I mostly just carried the carcass,” he said.

A little over two decades ago, the 2,000-pound animals returned to the site of their holocaust. At first numbering just a few dozen, tribal leaders, local groups and international organizations created the chain that has pulled in more than 300 of the animals back to their home on Montana’s prairies. They bison herds have replenished themselves enough so the tribe can offer regular hunting licenses.

Unlike the silos, pick-up trucks and rows of crops, the bulls, cows and calves blend in with the waving grass that stretches into the sky. Outside of the occasional sparring match between bachelors, they mill and eat as quiet as the wind.

Two separate herds graze at Turtle Mound Ranch, tended by seven members of the Fort Peck Fish and Game Department. Along with the administrative apparatus that brought bison back to Assiniboine and Sioux nations at Fort Peck, the ranch gets its share of visitors in and out of the tribes. They include onlookers and hunters.

The ranchers of Turtle Mound Ranch ride horses built by General Motors. The jagged tracks that loop around the prairie make it nearly impossible to navigate without hooves or four-wheel-drive. It’s a naked bit of land colored by the seasons: green in the spring summer, yellow in the fall and stark white for most of the winter.

To a body that hasn’t acclimated yet, or lacking a brown coat, the cold wind that comes blasting from the northwest as late as March stings and stifles.

Robert Magnan, comfortable in the last remnants of winter in mid-March dressed in just a flannel and a cap bearing the logo of the 82nd Airborne, has spent nearly every day of the past 20 years at Turtle Mound Ranch, and he’s overseen more than 1,500 hunts.

The director of Fort Peck’s Fish and Game Department, who saw a buffalo for the first time as a boy at a Denver zoo, had to wait 30 more years until he saw one outside of a cage.

The first group of buffalo arrived at Fort Peck in the year 2000. One hundred animals, all coming on an initiative launched by Magnan, arrived from Fort Belknap. Although a boon to the local economy for the tribes who earned money from annual hunts for the animals, all of the animals from Fort Belknap retained a trace of cattle genes. About 80 percent of all buffalo in North America retain trace amounts of cattle genes, a throwback to when agricultural specialists tried to dilute what few buffalo remained.

Magnan and the rest of the tribe had to persevere through 12 years of litigation until buffalo from Yellowstone National Park arrived in 2012, genetically pure and meant specifically for cultural rehabilitation.

This makes Turtle Mound Ranch only one of four places in the world that house pure-blooded buffalo.

The plan was initially met with resistance from cattle and property interests who lobbied against bison on the grounds that they would be too difficult for the tribes to contain and their presence risked the spread of brucellosis. The degenerative disease introduced first by cattle has been found in the elk of Yellowstone National Park, and its threat spurred a three-year quarantine program.

The program takes buffalo that would otherwise be culled, killed to prevent the potential spread of brucellosis at Yellowstone. The national park reports culling between 600 and 900 buffalo annually.

Magnan, whose father is Sioux and his mother Assiniboine, said in the eight years since bison have come from Yellowstone to Fort Peck, cows have gone from there to the Crow and Blackfeet nations in Montana.

“We had what we call the economic herd for the first few years, with revenue from hunts making the tribes good money. But after a few years, it was pretty clear that money wasn’t enough,” he said.

The cattle lobby still pushes against their presence on Fort Peck or any nation. The same week that the United States Agricultural Administration arrived at the ranch to take blood samples to ensure that those under quarantine remained free of brucellosis, a lobby representing property owners in the state filed a lawsuit.

According to the lawsuit, brought against the state’s Department of Environmental Quality, a study released by the department centered on the environmental impact of the buffalo showed the animals’ limited detriment on the surrounding land.

The lawsuit joins dozens of others filed by property and cattle interests over the past 20 years.

“It’s prejudice. I hate to say that, but that’s what it is,” Magnan said.

Buffalo, silent and indolent on the ranch, have adapted to thrive on Montana’s prairies. They need only three things to survive: food, water and minerals. They find all they need in the roots and creeks that carve through the property.

“They make due with incredibly little,” Magnan said.

Sparring sessions break out and break down in seconds among the younger males. Matriarchs head the packs. Males stand facing north in winter.

Magnan said he’s seen family groups as big as 100 strong.

Magnan had to wait until his 40s, after serving in the 82nd Airborne, on the tribal police and attending a few years of college until he saw his first pure-blooded buffalo.

The plan was initially met with resistance from cattle and property interests who lobbied against bison on the grounds that they would be too difficult for the tribes to contain and their presence risked the spread of brucellosis. The degenerative disease introduced first by cattle has been found in the elk of Yellowstone National Park, and its threat spurred a three-year quarantine program.

The program takes buffalo that would otherwise be culled, killed to prevent the potential spread of brucellosis at Yellowstone. The national park reports culling between 600 and 900 buffalo annually.

Magnan, whose father is Sioux and his mother Assiniboine, said in the eight years since bison have come from Yellowstone to Fort Peck, cows have gone from there to the Crow and Blackfeet nations in Montana.

“We had what we call the economic herd for the first few years, with revenue from hunts making the tribes good money. But after a few years, it was pretty clear that money wasn’t enough,” he said.

The cattle lobby still pushes against their presence on Fort Peck or any nation. The same week that the United States Agricultural Administration arrived at the ranch to take blood samples to ensure that those under quarantine remained free of brucellosis, a lobby representing property owners in the state filed a lawsuit.

According to the lawsuit, brought against the state’s Department of Environmental Quality, a study released by the department centered on the environmental impact of the buffalo showed the animals’ limited detriment on the surrounding land.

The lawsuit joins dozens of others filed by property and cattle interests over the past 20 years.

“It’s prejudice. I hate to say that, but that’s what it is,” Magnan said.

Buffalo, silent and indolent on the ranch, have adapted to thrive on Montana’s prairies. They need only three things to survive: food, water and minerals. They find all they need in the roots and creeks that carve through the property.

“They make due with incredibly little,” Magnan said.

Sparring sessions break out and break down in seconds among the younger males. Matriarchs head the packs. Males stand facing north in winter.

Magnan said he’s seen family groups as big as 100 strong.

Magnan had to wait until his 40s, after serving in the 82nd Airborne, on the tribal police and attending a few years of college until he saw his first pure-blooded buffalo.

“They’re not wild. There’s no such thing as a wild buffalo. We call them wide ranging,” he said.

The buffalo of Fort Peck have a range as wide as 25,000 acres to wander.

Magnan said that four years ago, an injured bull laid down and died. The bull, who he and the other ranch employees named Elvis, came to Turtle Mound Ranch courtesy of one of Ted Turner’s herd. They left him where he fell to try and draw out a black bear loose in the area. When Magnan and rangers reviewed field cameras, they didn’t see the bear. They saw more buffalo.

Four younger bulls sat in a ring around Elvis for days. When Magnan brought the news to elders, they told him that it coincides with the story of a soul wandering the earth for four days before it leaves.

“That’s when I started to think that maybe they do have a soul,” he said.

Magnan said other behavior reinforces his, the elders’ and much of the two nations’ belief in the buffalo being more than animal. They refuse to scatter when one of their own is shot. When a family group senses danger, they form a horned circle around the calves.

Along with hunts, Magnan has overseen naming and burial ceremonies for the buffalo in the cultural herd. He said he’s seen the spiritual benefits of their return to Fort Peck in the women who cry when they break loose from the trailers hauling them from Yellowstone, and in the love of his job that’s made him put off retirement for another few years.

Robert McAnally, a founder president of Fort Peck Community College and the current head of gaming for the Sioux and Assiniboine, joined a handful of researchers from Montana State University to conduct hundreds of hours of interviews with enrolled tribal members in 2014. Questions focused on the therapy, what the authors called “reciprocal restoration,” for the Sioux and Assiniboine from the restoration of the buffalo.

McAnally saw his first wild bison at Yellowstone National Park when he was still a boy. He and his family traveled to the park one summer, and stopped to see the last of the original herd from the 1890s. Those came from the only few dozen left from the massacre of the bison during the previous century, when commercialized hunting obliterated their population from over 30 million to just 1,000.

The 7-year-old who would eventually become a navy veteran, University of Montana graduate, lawyer and Fort Peck Community College’s first president didn’t know what he was looking at when he saw the 2,000-pound animals milling around the park.

“Their importance hadn’t been taught to me yet. I hadn’t learned that we were related to them,” McAnally said.

Along with the study on the spiritual benefits of the buffalo, McAnally also served on a committee that produced a history of the Sioux and Assiniboine from 1800 to the 20th century based on thousands of documents. The history of the buffalo, McAnally said, coincides with the Sioux and Assiniboine.

“Eventually, the United States Army determined, in that era of the 1860s, 1870s, that the way to beat Indians was not to engage them in battle,” McAnally said. “It was to take away our spirituality, our food source, our clothing source. That one animal provides most of all the things we needed, especially spirituality.”

In 1875, the U.S. government assigned the Assiniboine of northeast Montana to what was then the Milk River Agency. Letters between U.S. Army officers reported that they had enough buffalo kills to last them through the winter. Unlike the Sioux, and other tribes outside of the agency, the Canoe Paddler and Red Bottom bands of the Assiniboine maintained somewhat respectful relations with the federal government.

None of that rapport kept Generals Sherman and Sheridan from crippling access to buffalo for all of the plains Indians. While limiting access to guns and ammunition to hunt, the United States government put out a premium on buffalo hides and tongues. Combining this demand for that of land in the American West, the buffalo bodies piled high and their population went from over 15 million to less than 1,000.

The pure bison on the prairie outside of Wolf Point, Montana are literally part of the land. The same species left bones behind in the sediment that date back to the retreat of the glaciers during the Ice Age.

Bison, even those with cattle in their genetics, act independently from their bovine relatives. They don’t chew the grass down to the earth. They mill around. Another study authored in 2012 by the Fort Peck Sioux and Assiniboine member and University of Montana graduate student Michel Kohl, now assistant professor at the University of Georgia, found that buffalo extend their territory as far as they can.

The explosion of cattle across the North American continent undid an ecosystem that relied on what Kohl called the “patch mosaic” provided by the bison that shaped the livelihoods of those dwelling in the prairie, both human and animal. While the nearly 100 million cattle in the U.S. operate on a system that has them concentrated to specific grazing areas, bison historically grazed an area briefly and sometimes would not return for another five years.

Although many have become accustomed to using the terms interchangeably, bison are considered native to North America, while buffalo originated in Asia and Africa. However, mixing bison with cattle created a breed that both requires more water and has coincided with the decline of other species native to the Great Plains.

“Grassland birds are one of the fastest declining groups of animals on the planet,” Kohl said. “Within the Northern Great Plains, we’ve seen a number of our endemic species drastically declining. In most cases, this can be attributed partially to habitat loss, but also, there’s ideas out there that it might be due to this large-scale loss of patch grazing across the landscape.”

Matthews, the tribal member who has sworn off killing buffalo, still spends much of his time focused on the animal.

His wife of more that 40 years, Moon Matthews, collects saltshakers. Rows of porcelain cats, dogs and unicorns flank photographs of children and grandchildren. Around those photos sit indications of a busy life. Commendations for police work sit next to sheriff’s badges. A purple heart stands next to a certificate for a bronze star.

Photos of Matthews, his wife and his family show his lifetime of a logger, soldier, jailer and policeman all ending with the man reclining on the couch draped with the buffalo hide. He’s let a grey mustache decorate his face, and the black hair shown in his wedding photo has receded some and turned a similar grey.

The hide stretches across the couch in the home that he and his wife moved into after his retirement. The tail dangles off one of the arms. After more than a year, it’s still soft to the touch, not quite as coarse as a cowhide, but still thick enough to trap in the heat of all that it covers.

“I wanted to use it as a blanket, but my wife refused to have it in the bedroom,” Matthews said.

Matthews served in the U.S. Army for 13 years, and that included three tours of Vietnam. Two were with the 25th Infantry Division.

The wounds that couldn’t be seen, post-traumatic stress, didn’t bubble up to the surface until recently. It comes in dreams, memories of friends lost. He finds therapy in the rifle sitting next to him on his couch.

“I go shooting. It calms my nerves,” he said.

He also finds therapy visiting the bison on Turtle Mound. He said he still feels a tinge of guilt visiting the ranch, like the buffalo he came to sit and watch might be judging him for what he did.

“I don’t feel that way about anything else,” he said. “Not about any animal.”

Out on the ranch, a pure-blooded bison was standing by a frozen stream. It could very well be one from the spring of 1820. It’s this very scene, blending the history of the land, its people and the spirit of the animal so revered by both, that Matthews has solace. “I could spend all day there,” Matthews said.