Caring For Indigenous Montanans Trainings Reach Health Care Workers

A resource offered by Montana State University’s Montana Office of Rural Health and Area Health Education Center that aims to improve health care for Native Americans in Montana reached more than 1,500 health care workers and students in its first year.

Because of historical experiences, some Native Americans may feel hesitant to trust health care institutions. That’s why creating resources that build understanding and respect is so important, said Grace Behrens, project coordinator with MORH/ AHEC. That distrust has tangible impacts, Behrens said. According to MSU research, the life expectancy of Indigenous people living in Montana is 19 years shorter than that of white residents. Native populations see disproportionately higher rates of diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure and other chronic illnesses, and significantly worse maternal and infant health outcomes.

That’s why MORH/AHEC, which is housed in MSU’s Mark and Robyn Jones College of Nursing, created the Caring for Indigenous Montanans trainings to disseminate across the state. “It’s directly tied to health outcomes,” Behrens said. “We know that sometimes people delay or avoid care when they don’t feel like they’re being treated well in the health care system.”

Created with funding and support from the Montana Department of Health and Human Services, the free online text and video trainings are available to anyone working in health care.

Since its launch in August 2024, more than 1,500 individuals have completed the course, which has received positive feedback from Native Americans and health care providers.

“Trust is at the heart of effective health care. By centering Native perspectives, we can strengthen connections between Montana’s current and future health care workforce and the communities they serve,” said Kailyn Mock, director of MORH/ AHEC.

“What we’re hearing is a lot of appreciation that there’s a resource out there that reflects different Native communities and how they want to be seen,” Behrens added.

The course includes eight trainings specific to each tribal government in Montana. Existing resources tend to lump all tribes together, Behrens said, and “paint with too broad of a brush.” Recognizing that health care providers are unlikely to complete all eight trainings, Behrens recommends that they take the courses about the communities closest to where they practice.

The project started in 2023 and was led by Stephanie Iron Shooter, director of DPHHS’s Office of American Indian Health, who grew up on both the Fort Belknap and Rocky Boy’s reservations and is Aaniiih (Fort Belknap) and Sicangu (Rosebud, South Dakota).

Iron Shooter said it was the first time DPHHS had created comprehensive health-oriented resources specific to each reservation, and it was important to do it right. That meant receiving permission from each tribal government for the project and honoring each nation’s unique history. The curriculum was crafted in partnership with Montana tribal leaders and cultural knowledge keepers, who helped workshop the written text of the modules to ensure they were culturally relevant and reflected key points.

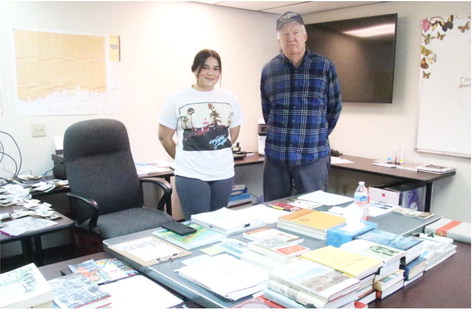

The tribes also connected project leaders with people who were willing to share their personal stories. In summer 2023, Behrens and Iron Shooter traveled to each reservation in Montana and conducted more than 70 interviews for the videos, which were filmed and edited by Lex Harold, a graduate student in MSU’s School of Film and Photography.

“Storytelling has been a traditional way of expression for many Indigenous people for centuries. We took the voices of Montana tribal members and incorporated them into every piece of this training,” Iron Shooter said.

Each course includes interviews with Native community members and contextual information from Joseph Gone, an anthropology professor at Harvard University and former Katz Family Chair in Native American Studies at MSU.

Practitioners who complete the course are given practical advice about caring for Indigenous patients. For example, they learn to make time for storytelling from patients and listen to what a person is experiencing. They are also advised to recognize the importance of generational Indigenous practices and healing ceremonies.

“That was one thing we heard a lot, was folks wanting their traditional ways of being healthy to be just as respected,” Behrens said.

The video trainings offered by the program cover Native American history and many related topics, such as the near extermination of the buffalo and the history of government-run boarding schools.

Iron Shooter encouraged health care providers to visit clinics on reservations, meet members of the tribal governments and attend Native cultural events.

“Come and get to know us as a people, as cultural keepers of our way of life. Come and get to know us so that we can work together to build trust,” Iron Shooter said. Simple gestures can also go a long way – for example, if a provider has photos of Native Americans on their walls or displays the flags of nearby Native nations, that can show people they are welcome in that space, she said.

Now, a year after the resource was launched, organizers are gathering feedback about the courses and evaluating potential adjustments. Regardless, Behrens said the resources were purposefully built to be expanded upon later. “This was a really unique partnership between the state health department, the university and all eight tribal governments,” Behrens said. “It just really shows the impact we can make when we all work together.”

People can access the free trainings online at healthinfo. montana.edu/cfim/index. html.