Political Headwinds Turn Against Wind Farms In Southeast Montana

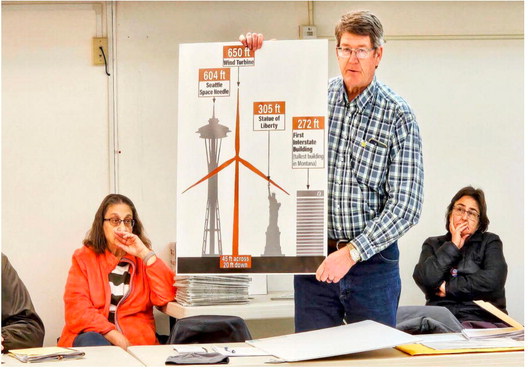

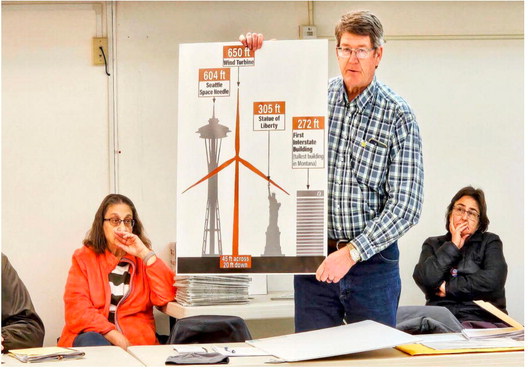

TERRY — The landman who knocked on Rolane Christofferson’s door in 2018 didn’t have to give her a hard sell on the compatibility of wind farms and cattle, or how she would adapt to hosting a structure on her property taller than Montana’s tallest building, the 20-story First Interstate Bank Center in Billings.

Christofferson’s challenges cast longer shadows. The bills for her mother’s stay at Prairie Community Nursing Home were piling up. To cover those costs, Christofferson and her siblings had to sell some of the land her Czechoslovakian grandfather had settled in 1906.

“The reason we signed the lease was mainly to cover the hospital bill, because we didn’t know at the time how long she would be there,” Christofferson said. “At $6,000 or $7,000 a month, it doesn’t take very long to run up a really big bill.”

Other area landowners who were approached about hosting parts of the 800-megawatt project had similar needs. Lisa Everett was trying to hold on to the land she had ranched with her husband before he died.

Everett’s calculations indicated she wouldn’t be able to pay off the note until she was 80, and that was with the help of her new husband’s income as a cattle truck driver. A little piece of the $1.85 billion project known as Glendive Wind had to help, she said.

The leases were signed in 2018 with Orion Renewable Energy Group. Not long after, the project was sold to Florida- based NextEra Energy, the largest electric utility holding company in the United States. NextEra developed a 775-megawatt wind project between Miles City and Forsyth that includes a footprint in three counties. A new 80mile transmission line was built to deliver NextEra’s electrons to the substation in Colstrip, which delivers power to the legacy shareholders in Montana’s 40-year-old coal-fired power plant.

Glendive Wind was next. Leaseholders in McCone, Prairie and Dawson counties started thinking about potential paychecks.

“A lot of it depends on how many turbines are put on your land,” Christofferson said. “And then if you have a substation, or if you have lines running from the substation through your land, you’re paid for that. I just heard that one guy in Garfield County was getting like $140,000 a year. So I’m thinking he probably has quite a few turbines.”

Christofferson and five family members had signed a lease for one turbine.

But something was astir, and it wasn’t the wind. By 2024, southeast Montana residents began pushing to stop the project. Residents of reliably Republican counties who normally supported minimal government regulation began lobbying for countywide zoning — virtually unheard of in Montana — to sandbag wind energy development through county permitting. They argued that neighboring property owners had viewshed rights.

“Can I pull up in Miles City at midnight, liquored up, and blast my radio? No, an officer’s going to come by and shut that down. I don’t have that right to interrupt a man’s sleep,” said Dennis Teske, a Prairie County commissioner who opposed the wind farms.

Speaking at a commission meeting July 16, Teske rattled off a list of concerns, including encumbered views, sunlight flickered by turbine blades, shadows, and potential magnetic and radio wave interference.

At its emotional peak in the fall of 2024, debate at local government hearings swung to “wind turbine syndrome,” a long-debunked claim that wind turbines emit frequencies bad for human health.

By late November, the state Land Board, comprising Montana’s five statewide elected officials, was tabling discussion of including state trust lands in Glendive Wind.

And when Donald Trump again became president in January, terms favoring new renewable energy development in Montana were put on pause, starting with a Trump administration freeze on a $700 million grant for a new transmission line across southeast Montana and North Dakota to bridge the electrical grids of the country’s northwestern and midwestern states. Project developers, policymakers and think tanks working in the capital-intensive arena of energy development say a new Montana-North Dakota high-voltage transmission line could be a game changer for an area of the American West that’s seen limited expansion to its power grid in four decades. The North Plains Connector Line would be the region’s first major grid expansion since the construction of a 500-kilovolt line that carries power from the Colstrip coal-fired power plant to population centers in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1980s.

Montana’s congressional delegation leaned into reviving the state’s coal economy, which had been in decline through mine bankruptcies and power plant closures since 2016. It was all hands on deck for coal. Trump declared an energy emergency to rush federal coal permitting for Montana’s Bull Mountain Mine, which exports coal to Japan and South Korea. The EPA exempted the Colstrip power plant from Biden-era emissions standards. In July, Congress cut by half the royalties owed to federal and state governments for coal mined on federal land and ended production tax credits for wind and solar projects. Trump followed up by instructing the U.S. Treasury to strictly limit qualifications for the tax credit in its final months.

The Glendive Wind leaseholders were being left in the lurch.

Political fealty to fossil fuels is nothing new in Montana. The state’s last two Democratic governors insisted coal power was Montana’s energy future. Steve Bullock cried foul at then-President Barack Obama’s clean power plans for Montana.

Bullock’s predecessor, Brian Schweitzer, insisted that liquid fuel from coal would be Montana’s energy savior. When Arch Coal awarded the state an $86 million bonus for the right to mine coal on state land, Schweitzer pressed Montana’s left-leaning county commissioners to either support the mine or refuse the money.

In 2016, Republican U.S. Rep. Ryan Zinke arrived at Donald Trump’s primary election campaign rally in Billings with an RV full of placards that read “Trump digs coal.” Zinke was back in the state a year later with then Vice President Mike Pence, who declared that the “war on coal is over.”

But there has always been the caveat of support for a renewables-inclusive “all of the above” energy development policy, a phrase two-term U.S. Sen. Steve Daines still deploys frequently, though Daines consistently supports tax credits for coal and opposes credits for wind energy production.

Wind farms are “gold mines for tax relief,” said Tim Popper, of Prairie County, speaking at a July 17 County Commission meeting about a plan to decommission wind projects. Echoing a common public sentiment, Popper suggested that tax subsidies offered to wind farms have more value to developers than the energy they generate.

Residents testifying before the Dawson County Commission in opposition to Glendive Wind in the fall of 2024 suggested that the likely elimination of tax credits after Trump took office would kill the development.

NextEra project manager Ross Feehan, to the contrary, said the fate of Glendive Wind doesn’t hinge on federal production tax credits.

“Due to technology, artificial intelligence, data centers, demand for energy is going in one direction. It’s going up,” Feehan said. He likens Montana’s potential wind energy production to Texas’ Permian Basin, the largest oil-producing region in the United States, and notes that NextEra has additional Montana projects in the works.

There are several credible assessments of whether large-scale wind farms can be profitable without tax credits. The U.S. Department of Energy in 2024 reported that unsubsidized wind energy in the northwestern United States would need to sell for $47 to $49 per megawatt hour, meaning it would be competitive with power generated with natural gas, which the U.S. Energy Information Administration in May reported to sell for $40 to $60 per megawatt hour. The Montana Consumer Counsel put the cost of coal-generated Colstrip power for Montana customers at $54 to $73 per megawatt hour over a four-year period ending in 2017.

Several factors favor utility- scale Montana wind, starting with state laws in Oregon and Washington requiring utilities there to soon abandon coal power and phase out gas-fired power over the next 20 years.

Washington state utilities Puget Sound Energy and Avista Corp. will exit the Colstrip power plant at the end of this year, while keeping their share of the Colstrip transmission line. Both draw power from NextEra’s 770-megawatt Clearwater Wind project between Miles City and Forsyth.

Portland General Electric, a Colstrip owner slated to exit the plant no later than 2030, is both a Clearwater part-owner and a likely customer of Glendive Wind, according to NextEra and Portland General Electric. PacifiCorp, headquartered in Oregon, is on the same timeline.

Those Pacific Northwest utilities have held a 70 percent ownership share in Colstrip since the 1980s, when the power plant’s surviving units were built. Together, the Colstrip units have a nameplate capacity of about 1.48 gigawatts. Montana wind farm construction, which has added 1.2 gigawatts of nameplate capacity to Montana since 2020, is also driven by demand from Pacific Northwest utilities.

Puget Sound Energy will bring the 248-megawatt Beaver Creek wind project online Friday, Aug. 1, and has contracted with the 315-megawatt Haymaker Wind facility, which is expected to start construction in 2026 in Wheatland and Meagher counties and begin spinning in 2028.

The state requirements in Oregon and Washington remain in place even as federal energy policy changes.

Back in Terry, Christofferson and other leaseholders want their right to lease their property for wind development protected, even as Glendive Wind opponents protest. Nearby Wibaux County has adopted countywide zoning in response to a renewable energy project proposed by AES Global. Dawson County has drafted a countywide zoning plan that addresses not just wind farms, but tattoo parlors and marijuana dispensaries.

But what about property owners who partnered with energy developers before their neighbors began demanding a change in the rules?

“What are we supposed to do about the private property rights of the people who have contracts?” said Prairie County Commissioner Todd Devlin.

“I’m a photographer. The silhouette of a wind generation facility that’s 400 feet tall and modern-looking is not what I want to photograph, but I can’t tell my neighbors ‘you can’t build that,’” Devlin said.

Prairie County’s tax base would expand significantly with the development of Glendive Wind. Tax-exempt federal and state lands comprise nearly half the county. The taxable value of Glendive Wind would be 3% of $1.1 billion, Devlin said. A tax abatement for the project would cut into that revenue, Devlin said, but he doesn’t think commissioners are inclined to approve one.

Christofferson, Terry’s mayor since 2014, is ready for some economic prosperity. Energy booms linked to coal, oil and gas have touched some communities, but not others. Prairie County has been missed.

“I think zoning should be put in place to manage any development, not to completely stop that development,” she told county commissioners in July. (The city of Terry is unzoned, and has no zoning proposals currently under consideration.)

“We need to do something to make sure that our county exists longer. We don’t want to lose the hospital, we don’t want to lose our schools. We need to figure out some way to move forward, and I think this is an opportunity for us to do that.”

This story was reported in collaboration with the Glendive Ranger-Review newsroom as part of Montana Free Press’ 2025 Reporter Residency program, which places MTFP reporters for weeklong stints in community newsrooms throughout the state.