Legislative District Map Proposals Ignite Debates

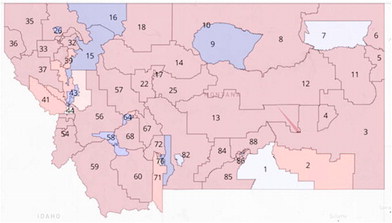

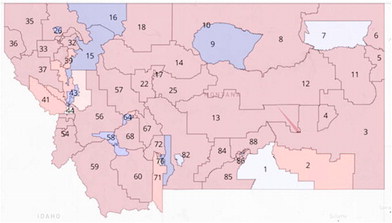

The four partisan members of the Montana Districting and Apportionment Commission introduced initial legislative district map proposals on Tuesday, Aug. 2, commencing debates about competitiveness and minority representation that will in part determine the complexion of the Legislature for the next 10 years.

The maps, one each presented by the commission’s two Republicans and two Democrats, wrestle with several thorny demographic questions that have emerged over the last decade — namely, how to address Montana’s rapidly growing, but unevenly distributed, population in a way that minimizes deviation between districts and addresses a set of both mandatory and discretionary criteria. In the background are major political considerations: Each of the 100 districts the commission draws by the end of the process will have some impact on the Republican goal of expanding an already substantial legislative majority.

Each party’s representatives on the commission addressed those various priorities in different ways. Democratic commissioners Kendra Miller and Joe Lamson brought maps they say prioritize competitiveness and proportional representation under criteria the commission previously adopted, while Republicans Jeff Essmann and Dan Stusek proposed plans they say put compactness, contiguity and minimal population deviation first.

Both maps from Miller and Lamson feature average population deviations of 0.8 percent, six majority-minority House districts centered around Native American reservations and 10 districts that have historically been won by either party at least 30 percent of the time, Miller said Republicans would be favored to win 57 of 100 House seats under the maps; they currently hold 67 seats in the chamber.

“One party has more power in this state, they have a majority — the voters are asking for that — but one party should not get extreme advantage above and beyond what the voters say they want,” Miller said.

The Republican maps feature similar population deviations, but depart from the Democratic proposals in their approach to competitive districts. The GOP approach is most evident in urban cores, as Republicans look to reverse the so-called spoke-and-wheel configurations of the 2010 maps that expanded Democratic-leaning districts from urban areas into surrounding suburban and rural regions that tend to lean right, ostensibly diluting the influence of those spokes.

The proposals from Essmann and Stusek would create more compact and densely populated urban districts; the Democratic proposals would create physically longer and narrower districts emanating from urban cores into various valleys.

Miller railed against the Republican proposals as partisan gerrymanders designed to isolate Democratic votes, even calling for the commission to not advance the GOP maps.

“Each of your maps have eight competitive districts total, but what is far more problematic isn’t that your map has fewer competitive seats in it, it is that there’s an egregious partisan gerrymander,” Miller said. “When your party is getting 57 percent of the vote statewide, on Commissioner Essmann’s proposal, Republicans would be favored to win 72 seats.”

Stusek, on the other hand, said the Democratic approach to urban districts disregards the functional compactness criterion.

“It didn’t seem that competition was the primary goal, it seemed that proportionality was the primary goal,” he said of the Democratic proposals. “There are 67 Republicans in the state House — to assume that drawing any more than 57 lean-R seats doesn’t make sense is not logical.”

The most obvious conflict was in the respective maps’ handling of racial majority- minority districts. While Miller and Lamson’s maps each have six House districts with majority Native American populations, Stusek and Essmann’s maps would each split a current majority-minority district. Stusek’s map splits a current House district that stretches from the Flathead Reservation to the Blackfeet Reservation; Essmann’s map would split a district currently encompassing the Rocky Boy’s, Fort Belknap and Fort Peck reservations.

“My objective here was to try to keep a community — the city of Glasgow — that has been divided for 20 years, intact,” Essmann said.

The Democratic commissioners said the Republican maps are blatant attempts at diluting Native American votes, and possible violations of the federal Voting Rights Act. Essmann and Stusek denied those claims.

“There’s been a question of representation and practical contiguity over the years [in the Blackfeet-Flathead district],” Stusek said. “You have to drive hours and hours to get across to represent your interests. I feel like I kept communities whole and in fact added communities to make a district that I feel would be compliant with the VRA.”

Early in this process, which began last year with the drawing of the state’s two new U.S. House districts, the commission adopted a series of mandatory and discretionary criteria.

Under the mandatory criteria laid out at the beginning of the redistricting process, the maximum average population deviation of all state House districts must not exceed one percent, the map must comply with the federal Voting Rights Act, the districts must be functionally compact, and they must be contiguous. Under the discretionary criteria — that is to say, desirable but not legally required — the commissioners may consider competitiveness between parties, no plan may be drawn to unduly favor one political party, the maps should avoid dividing cities, towns and other entities when possible, and communities of interest should be kept whole. Over the coming months, commissioners will continue to debate among themselves and also travel the state to gather public comment on the maps and make changes accordingly. Several members of the public have also submitted map proposals, with more to come.

“I almost guarantee you that we’re not going to have these same maps by the end of the process,” said Maylinn Smith, the commission’s nonpartisan chair and tie-breaking fifth vote. If, as has often been the case in this decennial process, the four partisan commissioners reach an impasse, Smith’s vote will determine the lines of the legislative districts, which are set to take effect beginning in 2024.

Miller emphasized that point, putting the onus on Smith to select a fair map.

“The chair will decide whether the map will reflect the will of the voters … or whether the game will be rigged in one party’s favor, subverting the will of Montana voters to hand power to one party that is above and beyond what the people of Montana are voting for,” she said.